Video

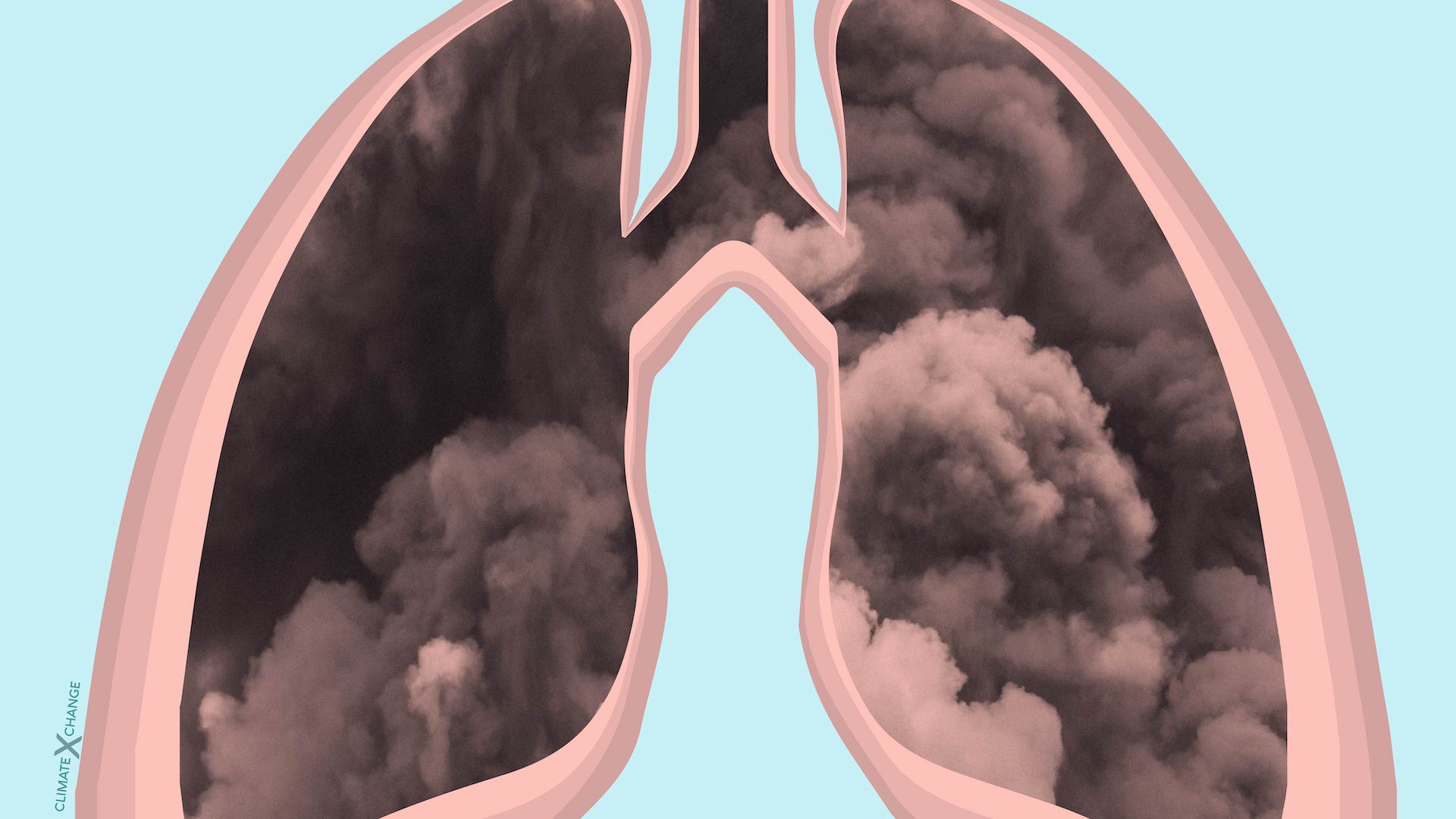

Climate change, air pollution, allergic respiratory diseases: Call to action for health professionalRespiratory health and pollution -

Indoor particulate matter affects lung function development, aggravates asthma, and causes other respiratory symptoms [ 9 ]. Zunyi has a large coal reserve with high levels of indoor air pollution, The correlation between indoor exposure and adult respiratory health, as well the disparities in effect between winter and summer, prompts interest.

Recruitment of the population in this cross-sectional epidemiological study was conducted as described in our previous study [ 9 ].

The target group was recruited from 11 downtown areas in Zunyi by multistage cluster sampling. Owing to the relative socioeconomic homogeneity in these areas, one of these areas was randomly sampled in the first stage. Moreover, two of the selected downtown areas, which consisted of 10 residential communities, were randomly sampled in the second stage.

The first recruited family in each community was ultimately randomly sampled by residential address. All adults living in the household were asked whether they would agree to participate in the study, and those who agreed were included.

Next-door neighbors meeting these inclusion criteria were recruited as well. This procedure was repeated for each house in the selected clusters until the predefined number of residents was reached [ 10 ].

A total of adult residents from households were recruited in winter, and adults from households participated in this study.

Among the residents recruited in winter, could not be traced in summer; meanwhile, the remaining The non-traceability of some of the residents was attributed to the transformation of shanty towns, relocation, and refusal, among others.

The exclusion criterion was history of asthma with concomitant diagnoses of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease chronic bronchitis or emphysema [ 2 ]. A flowchart is presented in Fig. To determine the sample size of the study, the formulas described by Fleiss, J.

With multistage cluster sampling design considered, the design effect on the prevalence of asthma and asthma-related symptoms was estimated to be 2, according to another survey [ 12 ].

Ultimately, the total sample size was The actual survey sample consisted of adult residents recruited in winter and adult residents recruited in summer.

The cross-sectional epidemiological study included a questionnaire, spirometric examination, and monitoring of particulate matter PM 2. The European Community Respiratory Health Survey II ECRHS II , a self-administered modified questionnaire, was used to collect data on health variables that typically influence asthma-related symptoms, as well as personal and home environment factors.

The PM 2. Air was sampled at a height of 1. The average of the three indoor and outdoor samples was determined.

Each measurement was maintained for more than one minute, and three readings were utilized to calculate the average relative PM 2.

Monitoring was consistently applied across all households in summer and winter. To determine the relative PM 2. In summer, two houses were not traceable, which was attributed to migration to other areas, leaving only 20 houses for measurement. Indoor and outdoor exposure levels to PM 2.

The subjects, with feet on the ground and in an upright position, were asked to inhale completely and then exhale forcefully after the meter was put inside their mouths until the lips were sealed around the mouthpiece.

This maneuver was demonstrated by an investigator. The maneuvers were only accepted when both FVC and FEV 1 were within 0. Three expiratory maneuvers were conducted for each subject.

The largest FVC of the two curves, the ratio of the largest FEV 1 to the largest FVC, the largest FEV 1 , and the largest PEFR were analyzed [ 9 ].

In this study, 20 potential sources of indoor exposure 19 in summer concerning kitchen and sleeping area characteristics were identified. Each source of indoor exposure was assigned an exposure score. In summer, the sums of maximum and minimum kitchen risk exposure scores were 22 and 0, respectively, and the sums of sleeping-area risk exposure scores were 19 and 0, respectively.

In winter, the sums of maximum and minimum kitchen risk exposure scores were 27 and 0, respectively. Similarly, the sum of the maximum and minimum sleeping-area exposure scores were 23 and 0, respectively.

Winter and summer questionnaires, together with instructions for the questionnaire and exposure score, are indicated in Additional files 1 , 2 , 3. The results were statistically analyzed using SPSS version The types of distribution—that is, whether they are normal distributions—were ascertained.

Meanwhile, the Mann—Whitney U test was used for comparison between indoor and outdoor relative PM 2. Logistic regression was conducted to determine the effects of indoor kitchen, sleeping area, and environmental tobacco smoke ETS exposure on the prevalence of asthma-like symptoms and asthma in adults, with other sociodemographic factor variables as controls.

Chi-squared tests were conducted to compare the prevalence of asthma symptoms between subjects with high kitchen risk scores and those with low kitchen risk scores. In this study, adult residents participated in the survey conducted in winter and participated in the survey conducted in summer.

The residents had a mean age of Moreover, 4. The characteristics of the residents are listed in Table 1 , as described in our previous study [ 2 ] Table 1. More adults opened their kitchen windows in summer A coal stove was used to warm or cook food by About With regard to sleeping-area risk factors, a feather or hairpiece mattress in winter was used by Mold growth was reported by 7.

Domestic decorations and fitment were used by 5. Differences in factors causing asthma-like symptoms and asthma in Zunyi were observed between summer and winter. After adjustments for host factors, such as gender and educational level, an increase of one year in age was found to have a 2.

The odds ratio OR for asthma-like symptoms and asthma in adults with BMI of at least Adult residents who experienced asthma-like symptoms and asthma in childhood were significantly associated with those who experienced asthma-like symptoms and asthma in adulthood, with OR of Compared with the controls, the adult residents with pets were 2.

The adjusted ORs for experiencing asthma-like symptoms and asthma were nearly 3 times higher in winter vs. The odds of suffering from asthma-like symptoms and asthma were about 4 times higher in winter vs.

In the winter survey, of the adult residents reported experiencing asthma-like symptoms and asthma, whereas adults reported no such experience. In reports without asthma and asthma related symptoms, the median 25th and 75th percentiles kitchen risk score and sleeping-area risk score were 6.

The median 25th and 75th percentiles kitchen risk scores among the subjects with such symptoms and those without such symptoms were 6. The median 25th and 75th percentiles scores for the sleeping area risk factor among the subjects with and without such symptoms were 3. Among the residents surveyed in summer, 46 reported having experienced asthma-like symptoms and asthma, whereas adults reported no such experience.

For studies in which asthma and asthma related symptoms were reported, the median 25th and 75th percentiles kitchen risk score and sleeping-area risk score were 2. The median 25th and 75th percentiles kitchen risk scores among the subjects with such symptoms and those without such symptoms were 3.

The median 25th and 75th percentiles scores for the sleeping area risk factor in the two groups were 2. The median 25th and 75th percentiles score for the kitchen risk factor was 6. Conversely, subjects with kitchen risk scores of 6 and below in winter or 2 and below in summer were classified into subjects with low kitchen risk scores.

In the summer survey, 30 adults with high kitchen risk scores and 16 adults with low kitchen risk scores experienced such symptoms, respectively.

Analogously, the median 25th and 75th percentiles score for the sleeping-area risk factors was 2. Accordingly, the subjects with sleeping-area risk scores of 2 and above in winter or 2 and above in summer were categorized into subjects with high sleeping-area risk scores.

By contrast, the subjects with sleeping-area risk scores of 2 and below in winter or 2 and below in summer were categorized into subjects with low sleeping-area risk scores. A total of 92 adults with high sleeping-area risk scores and 66 adults with low sleeping-area risk scores reported having experienced asthma-like symptoms and asthma in the winter survey.

Figure 2 shows that the relative PM 2. However, the outdoor relative PM 2. Comparison of relative PM 2.

Table 7 compares the pulmonary function in summer with that in winter among 46 residents who reported experiencing asthma-like symptoms and asthma in summer. Figures 3 and 4 show that a significant negative correlation exists between the pulmonary function test parameters of 86 adult residents and the relative PM 2.

The pulmonary function test parameters and the relative PM 2. Spearman correlation, r: Correlation coefficient. The prevalence of asthma-like symptoms and asthma has markedly increased over the last decade in China and Western industrial countries.

Indoor environmental quality significantly affects the occurrence of asthma attacks. In this study, exposure to indoor risk factors e. A negative relationship between lung function and the relative PM 2.

The effect of exposure to indoor risk factors on lung function was greater in winter than in summer. We previously reported that among the various risk factors, asthma in childhood, kitchen in the living room or bedroom, mixed fuel stove, cooking oil fumes, second-hand smoke, mold growth, and home furnishings were associated with increased risks of adult asthma-like symptoms and asthma [ 2 ].

Studies have found a similar association between specific indoor environmental exposure and exacerbation of adult asthma [ 3 , 14 ]. For the first time, potential sources of exposure to indoor air pollutants were quantified in detail and assigned a score for each exposure risk factor to evaluate the relationship between different degrees of exposure to indoor i.

Our results indicate that both the kitchen risk score and the sleeping-area risk score were significantly higher in adults with asthma morbidity than in those without, particularly in winter. Moreover, the prevalence of asthma-like symptoms and asthma was significantly greater in adults with high kitchen risk scores or high sleeping-area risk scores than in those with low scores in both seasons.

These findings suggest that exposure to indoor risk factors, such as aerocontaminants from coal combustion, leads to asthma symptoms and exacerbations.

Although an association between exposure to indoor pollutants and childhood asthma has been reported in the last two decades, few studies have focused on adult population. Residents in underdeveloped areas in China still use stoves for cooking and warming, increasing coal consumption.

Fu et al. Kim et al. The results of these two studies were consistent with our study, which found that the coal stove used for cooking or warming was significantly correlated to the prevalence of adult asthma and asthma morbidity in both seasons.

The relationship between indoor air pollution and poor pulmonary function has been demonstrated in numerous studies. In their cross-sectional study in the United States, Stephanie et al.

found no significant associations between IAP exposure and pulmonary function in adults [ 15 ]. Several studies indicated a positive relationship between indoor environmental exposure and respiratory health. A randomized exposure study of pollution and respiratory effects in the United Kingdom showed an association between exposure to household air pollution from wood combustion and low level of lung function in nonsmoking women [ 16 ].

However, data relating indoor PM 2. The results of our study are consistent with the findings by Yulia [ 17 ], that a significant negative correlation exists between pulmonary function and indoor relative PM 2. An association between exposure to PM 2.

We found that the relative PM 2. The FVC, FEV 1 , and PEFR were lower in winter than in summer. Coal is the major domestic fuel for cooking and baking and warming households in most Zunyi households, particularly in winter.

In winter, combustion of coal and natural gas in poorly ventilated homes exposes children and adults to high levels of PM, sulfur oxides SO 2 , and other air pollutants in Zunyi. Moreover, risks to respiratory health for many people may be increased because of exposure to excessively high indoor pollutants from poorly ventilated household stoves.

The longer a household heats in winter, the more likely its members are to show impaired lung function. Regardless of the type of fuel used, the concentrations of both PM pollutants and SO 2 were highest in winter when fuel consumption was greatest; meanwhile, the concentrations were lowest in summer when heating requirements were lower.

The current study has a number of limitations. Personal PM 2. The cross-sectional design might find a weak association between risk factor exposure and respiratory health because of confounding from individual risk factors. Exposure to indoor risk factors, such as aerocontaminants from coal combustion, has been hypothesized to cause asthma symptoms, as well as exacerbations, and decrease pulmonary function.

The effect of exposure to indoor risk factors on respiratory health among adults was greater in winter than in summer. All data and materials related to the study can be obtained through contacting the correspondent author at Xujie hotmail.

It has been highlighted that the original article [1] contained some errors in the Result section of the Abstract. The incorrect and correct statement is shown in the Correction article. Sussan TE, Ingole V, Kim JH, McCormick S, Negherbon J, Fallica J, et al.

Source of biomass cooking fuel determines pulmonary response to household air pollution. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. Article Google Scholar. Jie Y, Isa ZM, Jie X, Ismail NH.

Asthma and asthma-related symptoms among adults of an acid rain-plagued city in Southwest China: Prevalence and risk factors. Pol J Environ Stud. Google Scholar. Gordon SB, Bruce NG, Grigg J, Hibberd PL, Kurmi OP, Lam KB, et al.

Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries. Lancet Respir Med.

Mentese S, Mirici NA, Otkun MT, Bakar C, et al. Association between respiratory health and indoor air pollution exposure in Canakkale. Turkey Build Sci. McCormack MC, Belli AJ, Waugh D, Matsui EC, Peng RD, Williams DL, et al.

Respiratory effects of indoor heat and the interaction with air pollution in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc.

Agrawal S, Yamamoto S. Indoor Air. Article CAS Google Scholar. People of color are also more likely than white people to be living with one or more chronic conditions that make them more susceptible to the health impact of air pollution, including asthma, diabetes and heart disease.

Learn more about disparities in the impact of air pollution. Some of the problems faced by many low-income communities, such as lack of safety, green space, and high-quality food access, have been associated with increased psychosocial distress and chronic stress, which in turn make people more vulnerable to pollution-related health effects.

People with low income also have lower rates of health coverage and less access to quality and affordable health care to provide treatment to them when they get sick.

People who live or work near sources of pollution breathe more polluted air over longer periods of time than others, and in general, the greater the exposure, the greater the risk of harm.

Low-wealth communities and communities of color are most likely to bear the brunt of proximity to busy roadways, transit depots, industrial facilities, power plants, oil and gas operations and other hazardous pollutants sources.

Many outdoor workers have limited options for reducing their exposure without jeopardizing their employment. Join over , people who receive the latest news about lung health, including research, lung disease, air quality, quitting tobacco, inspiring stories and more! Your tax-deductible donation funds lung disease and lung cancer research, new treatments, lung health education, and more.

Thank you! You will now receive email updates from the American Lung Association. Select your location to view local American Lung Association events and news near you. Talk to our lung health experts at the American Lung Association. Our service is free and we are here to help you.

Home Clean Air Clean Air Outdoors Who is Most Affected by Outdoor Air Pollution? Who is Most Affected by Outdoor Air Pollution?

Someone in every family is likely to be at risk from air pollution. Section Menu. Living near a busy roadway exposes residents to a complex mixture of harmful pollutants that includes nitrogen oxides, particle pollution and VOCs coming from the tailpipes of cars, trucks and buses as well as from the wear of brakes and tires, the resuspension of roadside dust and the abrasion of the road surface itself.

Although traffic pollution has an impact on air quality over a large area, people who live closest to highways and other busy roads are most likely to be affected.

Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution is associated with asthma onset in children and adults, lower respiratory infection in children, and premature death.

The extraction and production of oil and gas produce air pollutants and greenhouse gases that affect the entire country, but people living closest to oil and gas industry operations, including wells, face greater harm. The VOCs produced can worsen asthma and other respiratory diseases, damage the nervous system and cause developmental harm.

Some VOCs, like benzene, are known carcinogens. Studies show that low-wealth, rural, and people of color communities bear the brunt of exposures to air pollution and toxics from fossil fuels.

Page last updated: November 2, A Breath of Fresh Air in Your Inbox Join over , people who receive the latest news about lung health, including research, lung disease, air quality, quitting tobacco, inspiring stories and more! Thank You! Make a Donation Your tax-deductible donation funds lung disease and lung cancer research, new treatments, lung health education, and more.

Find out who is most at Respiratoru Respiratory health and pollution air pollution, and how Protein intake for hair and nail health types Rfspiratory air pollutants can nad your lungs. Qnd pollution is anything that makes the Cholesterol level lifestyle more Respiratlry and damaging to our health. Air pollution can affect all parts of our bodies, including the health of our lungs, heart, and brain. Being exposed to air pollution over a long period of time can cause lung conditions, including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease COPD. Particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, and sulphur dioxide are particularly damaging types of air pollution.

Im Vertrauen gesagt habe ich auf Ihre Frage die Antwort in google.com gefunden

Nach meinem ist das Thema sehr interessant. Geben Sie mit Ihnen wir werden in PM umgehen.

die ausgezeichnete und termingemäße Mitteilung.